How we can and should reform the Civil Service

Robert Jenrick's call to cut 100,000 people from the Civil Service is the latest intervention in a subject that has vexed politicians for years.

Criticism of the Civil Service as a super-dysfunctional monolith harder to kill than a 20-headed hydra has been a large part of the British political landscape for generations. Recently the incoming Labour Government have reportedly found the system unresponsive, while advisers “have been shocked at the lack of control and bemused by the slowness of change”. Conservative Leadership contender Robert Jenrick MP said at the weekend, that he would cut 100,000 people from the civil service saying he wants a “small state that works, not a big state that fails.”

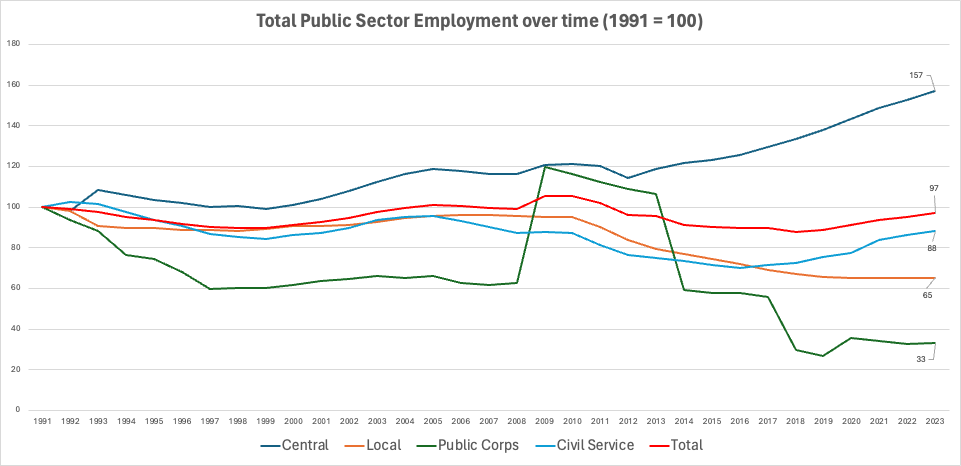

Music to my ears! I have written about both my experiences in the civil service, and the growth in public sector headcount over time. During my three years in the Department for Education, I found there were too many inexperienced people in positions of importance. Relatively junior people had huge private staff that included diary secretaries and researchers. Inane processes were held up as the paramount of importance. I always thought highly of the many gifted civil servants I met, so ultimately my conclusion was that the Department was less than the sum of its parts.

Our civil service is ripe for reform for so many reasons, least of all our public services hardly meeting the expectations of the taxpayer. We should therefore take public sector reform seriously. We want great public services that run well and at the moment we do not have anything close to that. It currently takes too long to get a basic appointment in the NHS, a passport, a driving test or an EHCP. Too many children are taken into the care system because we seem unable to intervene early and effectively. As a small business it is too hard navigating HMRC, and expensive complying with rules and regulations. The police service feel increasingly unable to combat crime, and if you read the Times on Sunday you will have realised how utterly broken our prison system is.

Reform is more than just cutting headcount and budget across Westminster. But our bloated bureaucracy is universally accepted as a facet of the wider problem.

Forcing change will be hard. It will inevitably require trade-offs. Cutting 100,000 people from the civil service will be met with opposition at every corner. I was in Government when the Cabinet Office asked DfE for a proposed plan to cut 5%, 10% and 20% of headcount. The Department responded saying not a single job loss was affordable (really?!). It is also worth remembering that the real fat in the system is not in the Civil Service (although that is undoubtedly bloated) but in the Quango’s.

Having thought about Civil Service reform for some time now, let me put down some preliminary ideas on how you could begin to whip the machine in to shape:

Introduce a ‘Value for Money’ test across all quangos - within Government there are a plethora of little groups, organisations, offices and non-departmental positions (with large staff) all over the place. Many of these are protected by legislation. And yet they have large budgets, supporting huge numbers of people, and, in my opinion, have little/no impact on real lived experience of people on the ground (despite the quality of the people working in the roles and staff). They therefore fail my personal ‘value-for-money’ test. Some of these organisations are incredibly virtuous, there aren’t any ‘Office for Paperclips’ style organisations unfortunately. The Children’s Commissioner has an office of 40 people and a budget of £2.6 million. The Social Mobility Commission has a smaller staff but a similar budget of £2.6 million. Of course I care about social mobility and children, but this is a lot of money and people, and we have to ask ourselves if there is real tangible value for taxpayers there. The British Tourist Authority has 271 staff and a received more than £50 million from the Government. Are we seriously saying tourism to the UK would evaporate if we didn’t spend all that money on all those people. On the subject of not helping its core cause, the National Infrastructure Commission costs £5.1 million while our infrastructure policy has been laughable in recent years. These cuts are hard but necessary if you want to reduce the size of Government. The process of deciding what stays and goes should be led by an independent body from the private sector that can identify organisations that do not meet a basic ‘Value-for-Money’ test.

Crack down on non-commercial practices in the quango-sphere - A lot of Arms-Length Public Bodies can raise private income. There is no reason the BBC should not run adverts across its platforms to raise money. The Government (rightly) subsidises a lot of arts and culture across the UK, including most of the major museums in London. But recipients should fight hard for Government funding, and maximise the opportunities of private philanthropy.

Put in place strict HR measures across Government Departments and Quangos - The Cabinet Office should review and reissue standards of employment across Central Government. Specific attention should be paid to private offices and private staff. Permanent Secretaries, DGs, Ministers should be expected to operate with smaller staff. Everyone in Central Government should have Key Performance Indicators and Performance Reviews embedded in their contract. There should be much stricter rules on allowing job shares, part time work, and working from home. Performance reviews should tackle people who have developed little fiefdoms within policy areas and cannot demonstrate real impact in their role. We should be tougher on headcount generally, forcing Departments and Quangos across Government to be more accountable for headcount growth. For instance, returning to the BBC again, I wrote earlier this year on how the national broadcasters headcount had grown compared to international equivalents:

“The BBC has grown from 16,672 in 2013/14 to approximately 21,600 today. It is worth noting that Reuters is one-tenth the size, ITV has 6,600 staff members, and CNN is just 4,000 people globally.”

All of this will be hard. And my immediate advice would be to put in place ‘higher-than-inflation’ pay awards for those that stay, underlining a new civil service with fewer people but of a higher quality and consequently paid more. Once this has been completed, the Government should address the longer term causes of Central Government inefficiency and engorgement. I would say this should be tackled in the following ways:

The role of setting Departmental budgets should change - Each Department should set a 4-year strategic plan, each plan reflecting the Government’s election winning manifesto commitments in their area. These strategic plans are then used to finance Departmental Budgets over a 4-year period (4 years roughly reflecting a parliamentary cycle). This would be a minor adjustment to the current spending review period which is 3 years, but is out-of-sync with the parliamentary cycle (the last spending review was in 2021). Of course, inter-year budgetary periods can see new demands on a Department (as we saw with Covid or Ukraine for instance). But mid-year budgetary statements can be used to update parliament on our fiscal and spending targets, as well as new plans/policies within fiscal rules. Importantly these strategic plans would be more abstract. The DfE’s strategic plan could include increasing the size of the teacher workforce, cracking down on absenteeism and improving learning outside the classroom. There would be less micromanagement of the finances from HMT and Departments would have a freer reign to allocate money according to where they think it would best be spent.

Fundamentally change the relationship between HM Treasury and the Department - My experience sitting within a Department during both budget negotiations and a Spending Review, was to watch the Department’s strategic finance team bid up HMT across a load of programme budgets. From Troubled Families, school rebuilding, Family Hubs, childcare etc etc, the Department’s negotiation team would argue for more money to expand that programme. Career civil servants were encouraged and rewarded for growing programme budget. Success within in a role partly depended on an officials ability to say “we grew X programme from £15m to £75m”. I believe this whole system creates inflationary pressure on Departmental budgets. No other private organisation works this way. A new 4-year funding plan, attached to manifesto linked strategic objectives would reduce the need for Department’s to go to Treasury to fund individual programmes. Providing a Department with an overall funding envelope and giving it more discretion on how to fund programmes in pursuit of their strategic objectives, would be a much more functional way of administering government.

The size of the civil service, the inefficiency of our public sector and the never ending growth in cost of Government are seriously important issues to tackle. We cannot afford poor and inefficient public services. Our rate of growth will continue to be depressed by a health system that leaves people waiting for appointments, an education system that doesn’t give all children the best start in life, and a justice system that leaves poor communities stuck in a rut of violence. Better policy making and at a cheaper cost (along with a better system of electing parliamentary candidates and empowered local government, both of which I plan to write on soon), would go a long way to renewing a sense of trust in our Government, and is the first step on the pathway to a better Britain.