So... how big is our Government actually?

Liz Truss now says a leftist bureaucracy is the biggest problem facing the UK... but to what extent is our state a big bloated mess?

Summary:

We all moan about excessive bureaucracy, bureaucrats, and the size of the state. An ex-PM has now decided it’s one of the biggest problems facing the British public.

However the size of our Government is smaller than it was when Margaret Thatcher left office. Some parts of Government have exploded in size, specifically quangos and some Whitehall Departments. There’s also been a noticeable growth in higher grade and higher paid members of the civil service.

Despite the proliferation of technology, big data and AI, productivity in the public sector has completely stagnated bringing in to question whether taxpayers are receiving any value-for-money from their public services.

Part of the justification for a ‘big government’ is increasingly complex and lengthy legislation and regulations.

So ‘PopCon’ launched yesterday. I didn’t attend, I have a fairly dim view of former Ministers and Prime Ministers trying to recharge a (divisive) debate on what the Tory Party stands for after 14 years in Government and just 10 months out of a general election. But that question is for another time.

One thing speakers railed upon yesterday were the ‘leftie structures of Government’ and ‘leftist group think’. Well this is something I can get on board with. One of the mini frustrations I came across while working in Government between 2020 and 2023, was both the super-sized and complex nature of working in central Government, and a world view that more Government and more money were the only way to achieve public policy aims.

The size of central Government departments, the number of people coming out of the woodwork to discuss a single policy issue, was also difficult to swallow. There were an extraordinary number of mid-level and senior civil servants who had ‘private offices’. Director Generals (DGs) and Directors would have small teams of staff following them around to meetings, taking notes, and chasing follow-ups. Asking for time with a senior official often meant being redirected to one their private secretaries. Deputy-Directors would have diary managers. I often wondered, when walking through the entrance lobby, how many people were actually analysts, lawyers, project administrators, who were involved in analysis, policy evaluation or implementation. I saw disturbingly little first-hand analysis while at the Department for Education. Often what I did see was second hand information generated by the Institute for Fiscal Studies or Education Policy Institute. You would have also thought such an emphasis on streamlining information and productivity for senior decision makers would improve decision making… there was no evidence that it did (but more on that another time).

There were a number of times when senior Ministers pushed the idea of reducing total headcount across Whitehall. The 2021/22 Spending Review made a commitment to reducing non-frontline civil service numbers to levels of 2019/20. These initiatives were often met with incredulity by the Civil Service. I remember on one occasion, the Secretary of State at the time commissioned the Permanent Secretary to look at at head count cuts across the Department. This was a response to a Cabinet Office push for efficiency and productivity gains across Whitehall (so it was a serious X-Govt initiative). The submission in response to the Secretary of State, thanked him for challenge, reiterated the Department’s intention to think seriously about efficiency gains, but admitted, there were ‘no viable options to cut anyone from the existing Department’. That is correct, the DfE though there were no head count cuts possible, without risking our ability to perform statutory duties.

How big is our Government?

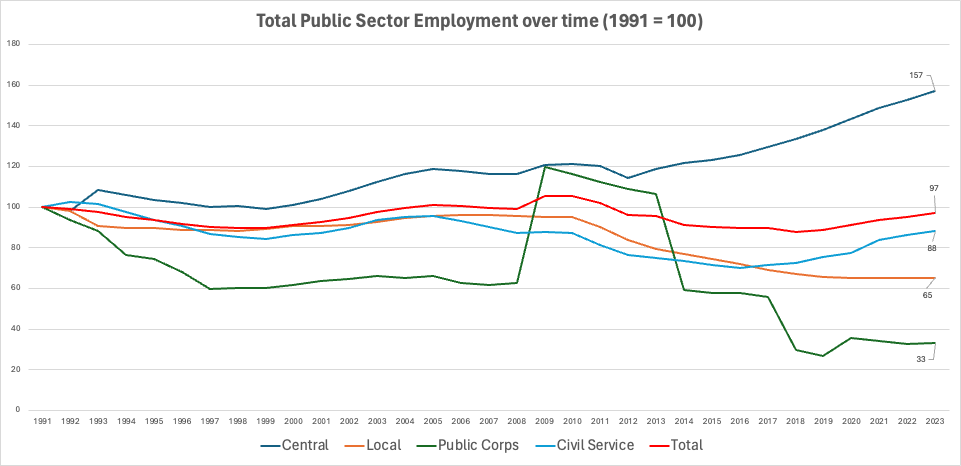

The British Government is indeed quite large. Over 6.4m people work in our ‘public sector’, roughly 19% of the UK workforce and 9% of the population. ONS separates out local, central, public corporations, and the civil service. There were 5.9 million people working across local, central and public corporations. The Civil Service makes up just 8% of total public sector headcount - 519,780 people, of which 487,665 work on a full-time basis. This is higher than it was 5 years ago, but lower than it has been historically. Since 2016 there has been a 25% increase in size of the Civil Service (approximately 106,000).

Outside the Civil Service, the number of people employed in Local Government has fallen fairly consistently from 3m in the early 90s to 2m in 2023. Central Government headcount has conversely increased fairly consistently in recent years. Between 1991 and 2011 total Central Government headcount (according to the ONS) fluctuated between 2.3m and 2.8m. Since 2012 the figure has risen from 2.6m to 3.6m, averaging a 3% increase in headcount every year for a decade.

Just to be clear, Central Government employment includes things sponsored by a Whitehall Department. For instance, HM Land Registry, The Crown Prosecution Service (CPS), Job Centre Plus, GCHQ, the British Army and the Houses of Parliament. But also more niche operations including the National Measurement and Regulation Office, Northlink Ferries connecting the Orkney and Shetland Islands to the mainland, and the Royal Airforce Museum, and PhonepayPlus (a regulatory body established to oversee the running of Premium Rate phone numbers in the United Kingdom).

In terms of total size though, our public sector has followed a similar trend to the Civil Service. It is has grown in the last 10 years, but remains marginally smaller than it was 20 years ago. In fact, today it is marginally smaller than it was in the early 90s when Margaret Thatcher left Downing Street. Local Government is 2/3rds the size it was, and the civil service is more than one-tenth smaller than it was when John Major took over.

In terms of our labour force, the UK public sector remains a large but diminishing part of our labour market. In 1991 total public sector employment was equal to 24% of the total workforce. By 2023 it was 19%. This has partly been driven by a smaller public sector, but mostly by a huge surge in private sector employment in recent years. The number of private sector jobs in the UK labour market since 2010 has increased by 3.3 million.

Comparing our bureaucracy to international competitors, the UK has a public sector (measured as a size of total workforce) smaller than some countries, mostly the Scandinavian ones – Canada (21% of the total workforce), Denmark (30%), Finland (25%), and Norway (32%). But the UK public sector is comparably larger than the public sector in the US (13%), Netherlands (13%) Germany (14%) and a few others.

Do we need so many people?

The trillion dollar question is whether we still need so many people (specifically in the Civil Service) to administer our state. The five largest Government Departments (MoJ, DWP, HMRC, MoD, and Home Office) are responsible for two-thirds of the total Civil Service workforce. Four of these five departments have seen a recent fall in headcount.

This is not true for all Departments, DCMS grew by 340%. since 2010. DfE, Cabinet Office, Treasury and DEFRA have also all grown. DfE grew by almost 5,000 civil servants between 2016 and 2023. Why DfE and DCMS headcount grew, considering neither had much to do with Brexit, is confusing.

The Institute for Government outlined what kind of roles saw growth, “Since March 2016, just before the EU referendum, the policy profession has grown by 15,565 staff – an increase of 94%. However, both the digital, data and technology profession and the analytics profession have also grown significantly – by 107% and 108% respectively, though the absolute increases in numbers are smaller than in the policy profession. The largest absolute increase in the number of civil servants since 2016 has been in the operational delivery profession, which has grown by almost 37,000 (17%)”. Civil Service statistics confirm there is a now greater representation of higher skilled (higher-paid) positions than there were 10 years ago (see figure below). Whether this is the accumulation of new people in higher skilled/higher-paid roles, or whether more people have been promoted to higher skilled roles without retiring more experienced staff members, remains to be seen.

The largest public sector employers outside of Whitehall include the NHS, British Army, Metropolitan Police Service, Network Rail and the BBC. Their growth reflects the the wider trends across non-departmental public bodies (and the political priorities that have developed int he aftermath of the Cold War).

The NHS is now the 5th largest employer in the world with almost 1.5 million people. It has increased in size by 26% since 2009 and by more than one-third since 1997. The BBC has grown from 16,672 in 2013/14 to approximately 21,600 today. It is worth Reuters is one-tenth the size, ITV has 6,600 staff members, and CNN is just 4,000 people globally. Network Rail has also grown in size from 36,000 in 2011 to 42,100 today The Metropolitan Police Service has grown from 28,000 in 2003 to 34,000 in 2023. The UK Armed Forces are the outlier here. The Regular Armed Forces was made up of more than 207,000 serving personnel in 2000. By 2012 this has fallen to less than 180,000. In 2023 there were just 142,536 serving personal in the Regular Armed Forces.

Whether we need so many people serving across our public sector is both a function of outcomes (are services improving.. which we will address in a future blog) and productivity (specifically whether each new recruit is as productive as the previous). The sad reality is that public sector productivity has stagnated for more than 20 years. The British public sector is no more productive today than it was 20 years ago, despite changes in size, technology, and increased funding. GVA per worker in the non-financial business economy , spurred on by the opportunities in the digital economy, grew by 20% between 1998 and 2019. In the public sector it was just 4%.

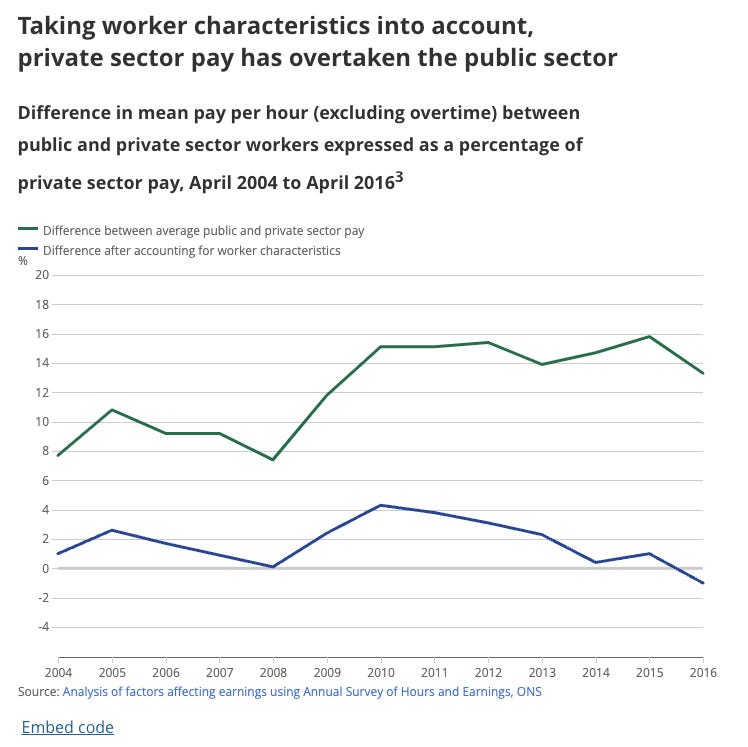

Pay in the public sector has historically increased in line with the private sector (up until the Covid-19 pandemic which hit private sector pay growth and the inflation crisis which temporarily hit public sector pay growth). And the ONS have produced some useful analysis which shows, that once you take worker characteristics into account (skill level/qualifications) public sector pay is broadly in line with private sector pay.

It’s not just about size, but also complexity.

As Governments have gotten bigger, so laws and public services have become more bureaucratic. The Economist recently stated that “the number of [US] federal regulations has more than doubled since 1970. The total word count of Germany’s laws is 60% larger today than it was in the mid-1990”s. The average number of pages for UK legislation has increased exponentially in recent years, from an average of 21 pages between 1950-80, to 86 pages between 2010-16. The total number of pages for all Acts and Statutory Instruments increased from less than 6,000 in the late 80s, to approximately 12,000 by 2016. The UK Office for Tax Simplification estimated that in 2012 the total length of legislation governing the tax code was 17,795 pages. Small businesses in the UK now have to comply with rules on workplace pensions, employers insurance, health and safety, grievance procedures, parental leave as well as register with the Information Commissioner, HM Revenue and Customs, Government Gateway and Companies House. The increased complexity in public administration and compliance has led to the need for more people to staff our public bodies. HMRC employs more than 60,000 people today. There are now one-quarter of a million people employed as NHS support workers (e.g. non-clinical), nearly 50% more than there were in 1997.HMRC employs more than 60,000 people today. There are now one-quarter of a million people employed as NHS support workers (e.g. non-clinical), nearly 50% more than there were in 1997.

As well as the increased cost of compliance to people and businesses, there is an increased cost to the taxpayer. The UK public expenditure was 45% of GDP in 2022/23. It has been more than 40% of GDP for all but two of the last 16 years. Low productivity rates have meant tax receipts have not risen at the same pace, leaving the Government to fill the hole with borrowed money. Public Sector net debt has risen from 21% in 1991 to almost 100% this year. The reality is that most Western governments have increased in size and public expenditure over the last 100 years.

And to the age old question of whether more public spending is good or bad for long term prosperity. The general consensus is that it is to a point. Livio di Matteo found that “Over the period spanning the first decade of the 21st century, after controlling for factors such as population size, per capita GDP, net debt to GDP, the institutional factors of governance and economic freedom and regional variations, there is a hump-shaped relationship between the government expenditure to GDP ratio and the growth rate of per capita GDP”. An article in 2007 entitled The Bigger the Better? Evidence of the Effect of Government Size on Life Satisfaction around the World found that higher rates of Government consumption reduce life satisfaction. Conversely an NBER academic paper published in 1999 find “larger governments tend to be the better performing ones.” Although this study included an examination of third world governments.

Conclusion

Forget PopCon… but the critique that Government is too big and bureaucratic deserves merit. Before you talk about the quality of public services delivered (for another day), there are all the hallmarks of a system that is unaccountable, un-dynamic and in need of reform. Despite huge improvements in the availability of big data, AI, mobile technology, diagnostic and assistive technology, online learning tools etc, our public sector still relies on a huge number of people to perform the functions of Government. Costs have risen, placing more burden on the taxpayers in the process. The criticism that ‘leftist group think’ has dominated policy making for over a generation also deserves credit, as we have seen quangos hoover up resources, creating an astronomic number of jobs in the process.