This is not just another NIMBY article

It's not whether we should build (spoiler alert... we should)... it's more about what we build and crucially where because we dont want to trash the countryside and we do want our cities to thrive.

I set up a Substack blog to write primarily about my time in Government but also as an outlet to discuss all things politics, economics, business and policy. I want it to be a resource of interesting topical writing that readers feel is value-add. Hopefully there will be a narrative that emerges. Expect lots on: efficiency and efficacy in public sector; why some countries and cities excel and others don’t; rural Britain; and other subjects. It’s free (of course) so please share with friends and encourage others to subscribe.

Best, Patrick

Who can bemoan Kier Starmer’s commitment, made in his conference speech last week, to build 1.5 million more homes in Britain. A lack of affordable housing is a critical problem that faces all corners of British society. Wealthy middle-class parents are increasingly on the hook to help their children with a deposit to get on the housing ladder. Aspirant young professionals starting a family are struggling to find affordable homes with the requisite number of bedrooms. Those without rich parents and good jobs are faced by a dwindling stock of social housing and a housing benefit system that is less generous than it once was.

Here are the facts: between 2005 and 2022 the average house in Britain almost doubled in price. Some places and dwelling types are worse than others – a terraced house in London has increased by a factor of nearly 2.5, whereas the cost of a bungalow in the North East has risen by less than a quarter. In the same period, wages have only increased by two-thirds. The problem of house price inflation outgrowing income growth is particularly pronounced for younger people. An IFS report published in 2018 showed that average incomes for 25-34-year-olds stagnated for over a decade. The ratio of median UK house price-to-income for 25-34-year-olds went from 4 in 1995/96 to 8 in 2016.

Considering the standard bank will only lend 5x young income, you can see home ownership has simply surged out of reach for many. In 1996, nearly half of those aged 25-29, and two-thirds of people aged between 30-34, owned a home. By 2016 those figures had fallen to 24% and 43% respectively.

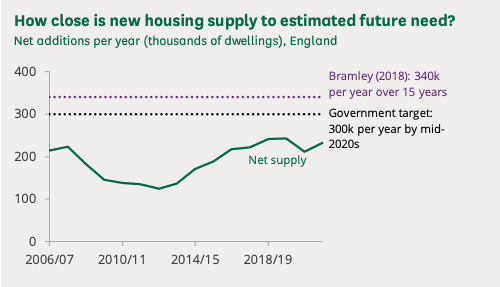

More houses are undoubtedly a good thing then. And it is an outrage that the Government have not got on top of the house building deficit that emerged in the 00s. The Government’s target of increasing the housing stock by 300,000 per year has never been met. Considering the population is going to grow at a rate that demands approximately 150,000 new homes per year, the situation will only get worse unless we build more homes.

So again, I say, who can argue with Keir Starmer’s commitment to build homes. But the more interesting comment he made was with regards to building on the green belt, “…where there are clearly ridiculous uses of it, disused car parks, dreary wasteland. Not a green belt. A grey belt. Sometimes within a city’s boundary. Then this cannot be justified as a reason to hold our future back. We will take this fight on”.

Has Labour thrown all consideration for the beautiful rolling hills of rural England out the window, I do not know. But his point does open the opportunity to state that the argument is not whether we need to build more homes, it is where we build them and what we build.

My hunch has always been that Britain has too quickly endorsed suburban sprawl as a means to expand housing. Drive along the M11 past Cambridge or the M1 past Milton Keynes and you will come across the familiar site of large housing estates, synthetically transposed on to a landscape, clearly awkward and out of place. All the efforts to make them blend in via shrub and vegetation, mixed use materials and varying patterns, are slightly futile.

In my own village, 30 minutes outside Ipswich and close to the Suffolk coast, a new development comprising 35-oddd units has sprouted up on the edge of the community. My problem with it isn’t just the disappointing aesthetic, but because we are a village without a school, a high street, a train station, a village shop or a petrol station. We simply don’t have the infrastructure to support 35 more families. More importantly we dont have anything to offer young aspirational families. The same problem is occurring 5 minutes up the road on the outskirts of another village which is made up largely of an NHS surgery and Spa outlet.

This frustrates me more because our local large towns of Ipswich and Felixstowe are in desperate need of regeneration. If you drive from the centre of Ipswich out towards Kesgrave you will drive through dilapidated undeveloped waste ground, low rise ex-industrial and terraced housing. There is no cultural or historical value there to be preserved (unlike the outskirts of pretty rural villages).

The fact is there are loads of small and large town centres that are in need of regeneration and redevelopment as a means of injecting energy back in to the area. Look at Bootle in Liverpool where traditional Victorian buildings remain dilapidated and unused, overlooking the docks and just 20 minutes from Liverpool Lime Street train station. Or Burnley which is a feeder town to Manchester, a growing population, but a sad and unenchanting town centre.

Data from the Centre for Cities shows “most new homes have been built in cities and large towns … About 803,000 were created in these places between 2011 and 2019”. However, 734,000 of those urban dwellings were built in the suburbs and only 69,000 were in city centres. Why were only 9% of new houses built in city centres when we know that is where young people, struggling to get on the housing ladder, more willing to live in flats and apartments, close to bars and restaurants, want to live. Young people do not want to live in the suburbs, they want to live in vibrant exciting cities and towns where they can walk from work to the gym, a bar, a gig and then home. Looking at towns that have grown fastest in the last 10 years, it’s a very odd bunch that doesn’t include Leeds, Manchester, Liverpool, Birmingham, Bristol, Oxford or Newcastle.

Returning to Ipswich for a moment, in the last 10 years the council have built 1,843 new build houses and just 78 conversions. The total increase in net supply of houses was 2,684 homes. In the surrounding East Suffolk area, there was an increase of 7,045 houses, most of which were new build homes. Mid Suffolk council increased supply of housing by 5,146 of which almost all were new build houses.

Instead of redeveloping Ipswich, increasing the number of affordable homes in renovated warehouse space, integrating it with educational institutions, new jobs in high growth areas, and cultural hot spots, we have built more than 10,000 bland suburban housing blocks in areas young people do not want to live, that add little cultural or economic value to the areas they were placed.

The Government knows town and city centres are struggling, especially after Covid. The cost of redeveloping units in urban centres is undoubtedly higher, but if we are going to spend the money, we might as well do it effectively. And the agglomeration benefits of creating thriving towns and cities where young and aspirational people can live, work, spend money and start up businesses will have massive value add for the economy in years to come. Its not rocket science, parts of Leeds, London and Manchester have led the way on urban redevelopment for years. The question should not just be whether we should build 1.5 million more homes, but how we do build those new homes and create thriving economic centres of the future too.