Poverty in Britain... how we measure it... why that's important... and how the left keep getting it wrong.

Is Britain poor? Has poverty gotten worse? Do we know how to tackle it?

On Thursday, Gordon Brown reared his head back on to national TV in an interview with Kay Burley for Sky News. I’m not sure why he was on TV, but there was a repeat performance of the same faux-humility we saw in 2010 and 2011 when he cracked jokes about ‘no longer being the future’ and his poor communication skills. However one clip caught the attention of social media, when Kay Burley asked him if was interested in perhaps getting back involved in British politics. He parried the question, of course, before saying:

“I am really worried about the state of poverty in Britain at the moment, and I really want people to focus on it, because you don’t hear any Government Minister ever talking about poverty, or about Universal Credit, or about how it needs to be reformed, and it is their duty to do something about it. Under their watch more than 4 million children in this country are in poverty”.

Cue some love-in from the standard-bearers of Brownism. This one stuck out in particular:

But it got me thinking about a subject that I spent a long time working on and campaigning over.

Firstly… is Gordon Brown correct to say that poverty is a huge problem and 4 million children in Britain live in poverty? There are two measures of poverty in the UK:

Absolute Poverty Measure - records the number of people and percentage of the population whose household income falls below a fixed threshold (whether that is the average income at a point in time or an agreed basic standard of living).

Relative Poverty Measure - records the number of people and percentage of the population whose household income falls below a moving threshold that is normally 60% of the median average salary.

Absolute Poverty is a more useful measure of changes to living standards over (long periods of) time. For instance the chart below shows the proportion of the global population able to live a basic standard of life has fallen consistently over the last 200 years. It is a useful reminder that in amongst a lot of conjecture about third world debt, global hunger, aid and criticisms of capitalism, generally the quality of economic life on this earth has improved in a positive and linear fashion.

Relative poverty is a better measure of economic inequality at a point in time. High incomes drag the arbitrary poverty threshold upwards, pushing more people under the poverty line.

Household incomes are calculated net of taxes and benefits. Meaning a policy to increase or reduce generosity of either can have a material effect on poverty stats. There is also a debate whether housing costs should be deducted, which is fair. But it is important which measure you use, because it will dictate which policies you deploy to alleviate poverty. Relative measures tend to lead to higher taxes and more redistribution, while the absolute measure tends to favour policies aimed towards long term GDP and productivity growth.

The IFS remain the national independent authority on poverty stats, in their annual Living Standards, Poverty, and Inequality Outlook (where they produce a relative and absolute poverty figure, before and after housing costs are taken into account). In 2023 it found that “The overall absolute poverty rate fell in the first year of the pandemic (2020–21) and was little changed in 2021–22, leaving it nearly 1 percentage point (ppt) or 480,000 people lower than its pre-pandemic level”.

Using the absolute poverty measure, poverty in the UK has fallen pretty consistently over time. This has been true for child poverty too. The percentage of children falling under the absolute line (after housing costs) has fallen, from approximately one-third in 2002/03 to one-quarter in 2021/22. In 2021/22 there were 3.3m children living in poverty, nearly 1m fewer compared to 20 years ago. So using the absolute measure, Gordon Brown is wrong.

The relative measure shows a fairly stagnant proportion of people and children living in poverty. It is fair to say at this point that, if you use a relative measure (say 60% of the average), statistical reasoning means the same percentage (one-third) of people will consistently fall under it (if you have a fair distribution of incomes). In fact for children, the percentage falling under the relative poverty line, 29.2%, was the same in 2001/02 as it was in 2021/22.

As the population has increased and the number of children in the UK has grown, so the number of children falling below the line has risen, from 3.8 to 4.2 million. So strictly speaking, the number of children in relative poverty has grown, and yes there are more than 4 million children living in poverty today, corroborating Gordon Brown’s statement.

If my subliminal message is not clear yet, let me explain… I believe Gordon’s statement and logic on poverty, are slightly duplicitous. It is an unavoidable statistical reality that as the population grows, more people will fall under a relative poverty line. It is also an unavoidable statistical reality that the relative poverty threshold falls as the economy contracts and average incomes fall, while it increases if the economy grows and average incomes rise. If you want to reduce relative poverty, as I mentioned before, you prioritise redistribution, but you also benefit when the economy stagnates.

I am not saying poverty is not a problem in Britain. Yes, pockets of poverty remain and the reasons why are clear. Housing costs have placed more pressure on lower income groups who haven’t been able to get a mortgage and own their own home, instead being stuck in the private rental market that has seen prices increase faster than incomes (see below). If you take housing costs out of the equation, there are 1.3 million fewer children in poverty in the UK. But generally, living standards have improved considerably and consistently in Britain, even in the last 20 years. And Brown’s use of the relative measure produces counterintuitive policy outcomes (as we will see later).

This leads on to why I believe it’s unfair to suggest Government aren’t talking about or acting to tackle poverty, because I think the Government has done a pretty good job in recent years.

Before 2010 Gordon Brown dominated the poverty debate with a viewpoint that poverty was relative, and could be solved by bumping household income above the arbitrary poverty line. He did this using tax credits for children, disabled people, and working people on low income. Tax credits supplemented more traditional forms of welfare - child benefit, housing benefit, unemployment benefits (Job Seekers Allowance) and incapacity benefits.

Budget after budget, Brown as Chancellor would use tax credits to boost incomes in the bottom half of the earnings spectrum, bumping as many people over the poverty line as possible. Each year more people would receive more generous awards. The average award of tax credits alone was £6,340 per year and by 2010 about 4.5 million people (including 4 million households with children) claimed them. And it achieved the desired effect. Between 1997 and 2010 there were 600,000 fewer children in relative poverty, and 2.2 million fewer children in absolute poverty.

But in reality the lived experience of people had barely changed. While incremental wage top-ups had helped push people over the poverty line, the trade-offs were huge - an expansion of the size and scope of the state, increased welfare dependency, more people unemployed (between 2001 and 2007 nearly 300,000 more people fell out of work despite strong economic growth), and an increasing prevalence of antisocial behaviour (such as truancy, teen pregnancy, cocaine abuse, gangs, family breakdown, specifically the increasing number of absentee fathers). A TV comedy-drama series Shameless, which depicted life on an estate in Manchester, came to symbolise the ‘new poor’. Another documentary series hosted by Anne Widecombe introduced the country to Mick Philpott in 2006. A father of 15 children who had never worked and ‘scrounged’ off the state, he later re-entered the national debate after he killed 6 of his children by starting a fire at his home as part of an effort to claim insurance money and get a larger council house.

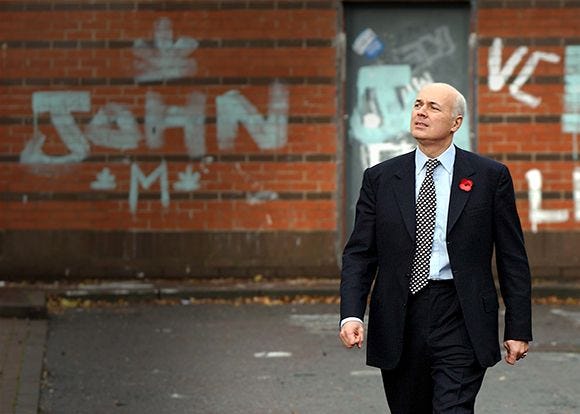

It was towards the end of the Blair Government in 2007 that the debate on poverty changed. Iain Duncan Smith MP had been the Leader of the Conservative Party before setting up the Centre for Social Justice. He said that no matter how many clever cash transfers a Government introduced, unless people had access to a good education, the dignity of a job, were free from debt and drugs, and lived a purposeful life for their their family and friends, they would never realise their own potential. He developed the idea of ‘5 pathways to poverty’ - a lack of a good education, unemployment, family breakdown, debt and addiction. If you tackled each pathway within one household, you would provide people with the power to live independent of the state.

This theory of personal change was backed up by American (liberal) economist and policy expert Isabel Sawhill, who established what became known as the ‘Success Sequence’. The Success Sequence dictates that for those who get a good education, get a job and then marry (hitting major milestones at the right time in life and in the right order), the probability of falling in to poverty is less than 1-in-20. The left hated it because the onus went from Government owning the solution, to people being held responsible. A ‘hand-up’ replaced the ‘hand-out’.

Under David Cameron, the Conservative’s completely changed their approach to disadvantage, social mobility and class. Talking about antisocial behaviour and young people, Cameron said society should ‘hug a hoody’. Once in Government, the CSJ’s work helped shape the Conservatives reform agenda in education, welfare, social policy, and focused their economic policy on job creation. I’ve spoken (here and here) at length on the great success of education reform during the coalition years. The success of the 2010-2015 Government in reforming welfare was equal in its transformational and positive impact (Perhaps something for a future blog?). As well as Universal Credit, the Troubled Families Programme was set up to help problem families get their life back on track.

The point in all of this is to accept that poverty remains a real problem in Britain but that policy has made a huge step in the right direction in recent years. More children receive a better education today than at any point in our history. The number and proportion of workless households has been on a downward trajectory, while the labour market has created nearly 4 million jobs since 2010. The number of children in Absolute Poverty, the traditional long term measure of living standards, has fallen by 2.5 million since 1997 (nearly halving).

Low and stagnant growth, paired with inefficiencies in the housing market will continue to put significant pressure on working families stuck in the private rented sector. Progress tackling gang crime, absentee dads, and exorbitant housing costs, are clearly still in need. But beware talk of idle Government Ministers. And seriously beware talk of returning to the failed dogma of pre-2010 which relied heavily on unaffordable and debilitating cash transfers. We know what works to help the most disadvantaged in society... it is an education, a job, freedom from debt, drugs, and crime, as well as being part of a community and family.