How to Get Big Things Done

Ca we learn how to do social policy from mega-infrastructure projects like HS2 and T5.

Summary

A new book provides an insight into how mega-projects can and do go wildly wrong.

There are some lessons from the world of mega-infrastructure that social policy experts and civil servants can learn from.

Plan, focus on aims, proper funding, quality leadership, well trained front-line delivery, data and culture change …. can all help programmes generate real social progress.

Most of us consider the HS2 situation (from concept, build time, cost, indecision over its future and the decision to cut it short) to be an absolute fiasco. A new book by Bent Flyvberg provides a glimmer of reassurance though because, as he says, the majority of big public projects overrun and under-deliver (in fact fewer than 1-in-10 ‘big projects’ are delivered on time and budget)! Phew… we are not on our own. All countries throughout time have messed up the delivery of new tunnels, power stations and the delivery of the Olympic Games (every Olympic Games since 1960 has gone over budget, by an average of 157%. The Montreal Olympics in 1976 went over budget by more 700%)!

Flyvberg and co-author Dan Gardner, use the book to offer some simple lessons for politicians and policy makers on how to get Big Projects done! And they are simple… planning is key (duh). Planning is the cheapest part of the delivery process and is too often rushed through. Better planned projects are often the ones where as many exogenous events can be prepared for. The authors also said plans should be developed by iteration… planners should ask themselves constantly whether the current incarnation works against the original aims of the project, and if it doesn’t in some way, to iterate plans, and improve them. Plans should be realistic (although he makes the interesting observation that realistic plans rarely get signed off…. Who would have signed off on HS2 if a realistic plan was submitted showing costs going above £100b). And finally, delivery should try and incorporate modularity as much as possible. Why? Because modular projects have proven to be cost and time efficient.

Flyvberg includes tons of interesting stories on the projects that went well (for instance, Heathrow T5 and Guggenheim Bilbao) and those that didn’t (the LA-San Francisco Bullet Train) as well as some useful stories of those that started badly but were turned around (Hong Kong MTR). He also points out the incredible cost-benefit of preventing unnecessary overruns. Hundreds of billions for an individual country, trillions globally. The benefit to the taxpayer would be huge and our temper would also be saved the frustration of reading about the next hold-up.

It got me thinking about what lessons we can learn in social policy. We spend hundreds of billions of pounds across social policy areas, from health, welfare, social security, education, and justice. I don’t think there is anyone across the policy world who thinks each £ across each project is totally efficient.

There is an astronomic amount of time spent in think tanks and Government questioning the real impact of programmes that want to reduce recidivism, or increase the birth rate, reduce truancy or boost community volunteering. The onus has always been on ‘what the evidence says’ but Flyvberg has opened a new avenue of criticising public administration on the basis of poor delivery. And I appreciate this, because I spent more time in Government worried about the same issues - will people use services available; will we train enough practitioners to meet demand; are we investing enough in data to maximise service quality. These were all questions of project delivery that determined whether our education and children’s social care systems performed above or below expectations.

Zooming out for a moment… questions on how we get children doing better in Maths at school, how we make our prisons safer, how we reduce waiting times in the NHS, deliver more dentists, and improve the time it takes to process a visa application, are increasingly about competent project management, before they are about more ‘traditional’ policy topics of taxes, incentives, subsidisation, and regulation.

So I thought about adapting Flyvberg’s lessons on big physical infrastructure and apply them to social infrastructure:

Plan and keep re-focussing on what the programme is trying to achieve - One of my major criticisms of Government is that it does things for the sake of doing them. Flyvberg notes this is as a problem in the world of physical infrastructure too… politicians love the idea of announcing big new ‘shiny’ projects because they are politically advantageous. New money announced for X, Y and Z, is the essence of retail politics. But too often in social policy, a programme designed to solve social problem A is based on dodgy evidence, underfunded, poorly developed and begins to take on a whole different meaning mid-way through the project. Family Hubs were originally conceived as physical ‘hubs’ within each community that would offer all parents support with problems they face as a family, which would jeopardise either their relationship or the wellbeing of the children. The problem was that evidence on whether the model would work solving family stability, was patchy: would the right people use them (remember Sure Start centres mostly attracted middle class mums looking for cheap coffee); will co-location of soft interventions that help a family deal with debt have a demonstrable impact on local family formation and stability? There was also serious disagreement across Government over what Family Hubs were for and what they would look like. What we ended up with was a patchwork of interventions predominantly aimed at young parents, across a number of different mechanisms (including an an online portal and). The money would then be given to Local Authorities who would give it to third parties who would build their interpretation of a ‘Family Hub’. But the programme was under-funded (it was always going to be), and the probability that we will be able to demonstrate an impact on family stability is inevitably unlikely. An alternative example were planning and focus has worked is in the Nuffield Early Language Intervention (NELI), which was well evidenced, and rolled out with the explicit focus of delivering extra hours of language support to children falling behind in school. The programme has now been operating for some years, and evidence shows that NELI children made the equivalent of three additional months’ progress in language skills, on average, compared to children who did not receive help.

Dont succumb to premature evaluation, manage expectations and be patient - The Troubled Families Programme had the admirable aim of helping the most problematic households in Britain by pairing them with a mentor and focussing families on developing pro-social behaviour. The early analysis was positive, but soon budgets were top sliced, and by the time I got in to Government in 2020, the programme had taken on a new name, and a new role of training support workers to triage other support workers and their families to front line services. This was neither the original design nor intention. The problem was that too many people wanted to see immediate results, when in fact the evidence base on the programme’s efficacy would build up over years. In America, a similar problem occurred during the 90s with the Moving To Opportunity Programme. The benefits weren’t felt for a generation (the evidence proved that MTO had a huge impact on social mobility), by which point the funding had been withdrawn. The loss to millions of families who would have benefited from MTO is a tragedy.

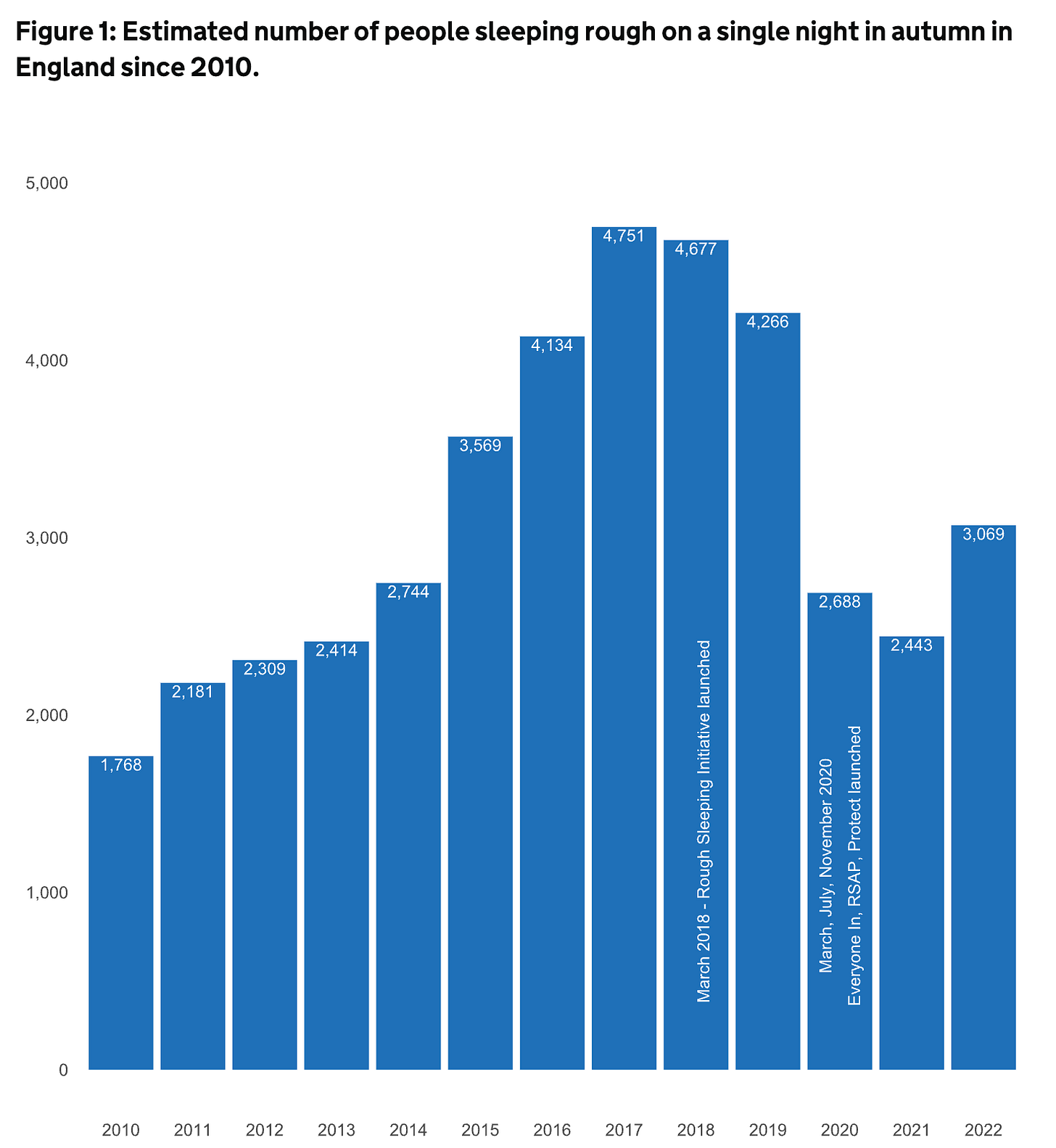

Things will always cost more than expected - Flyvberg makes the point about physical infrastructure that cost overruns are common in most projects (>50% of projects go over budget, and the average cost overrun is 62%). In the very worst situations, cost overruns can exceed 6-7x the original budget. Cost overruns are slightly rarer in social policy, because sunk costs are easier to hide. But the reality is that a lot of programmes are underfunded and consequently under deliver. This is because it takes a lot of money and a lot of effort to change complex social problems. A good example of this truism is evidenced in the impact of drastic increases in funding for rough sleeping and how that finally brought the rough sleeping numbers down. Today more than £300 million is provided annually to help intervene in the lives of people rough sleeping, before 2014 it is very difficult to find any money allocated to the problem at all. The chart below shows the impact that increased funding has had.

Motivated and quality people are critical to project delivery - This is a big one for me. I remember the CEO of a large City Council telling me that most policy problems can be understood and solved by looking at the people in mix. Is the programme being led by someone who is a real leader and visionary? Dame Louise Casey was instrumental in developing the early (visionary) model for the Troubled Families Programme. Kate Bingham was the incredibly driven and capable biotech expert who understood how to scale up development of a vaccine. It is not just about quality leadership, are the team behind them committed? Are front line workers committed, well trained and are there enough of them? I’ve written about Nick Gibb MP and Michael Gove MP leading the education reform movement with zeal and a maniacal sense of purpose. But there were hundreds of amazing Head Teachers (like Katharine Birbalsingh, Rachel Da Souza, and Jo Saxton) and thousands of aspiring teachers who would support the process of academisation, focus class time on academic rigour, and discipline across the school estate. So much about a schools success and failure comes down to the quality and commitment of teachers and school leaders on site. One of the reasons that quality people in the field is so critical is because it is almost impossible to scale-up a good idea without it. There is an amazing charity operating in Clacton called Lads Need Dads. It pairs young disaffected, at risk, boys with male role models, and has a superb track record of improving disadvantaged boys attainment at school and general life outcomes. It’s not over-the-top to say they hold part of the answer to solving the ‘boys crisis’ in Britain. But Lads Needs Dads succeeds because its founder and CEO is force of nature who has been able to create a culture of confidence and empathy among so many. Replicating its model elsewhere would need someone with the same special skill set… and that is rare.

Political leadership ensures longevity - Very much next to the point above, political leadership and sponsorship is key. The cause of education reform became a totemic part of the Conservative party’s reform agenda. As did the reforms to our welfare system spearheaded by Sir Iain Duncan Smith MP. His entire career for almost 10 years was focussed on reducing worklessness across Britain by rolling out Universal Credit. He stayed in post at DWP for 6 years, far longer than almost all his cabinet colleagues. And after leaving Government, as a backbench MP, he maintained pressure on Government to stand by his reforms. An example of where this has not been the case is the Opportunity Areas Programme. Announced in 2016 by Justine Greening early on her tenure, OAs were a promising place based programme that looked to solve entrenched problems of social immobility in an area. They didn’t work for lots of reasons (poorly designed, incoherence, and a lack of proper funding) but fundamentally, by the time I arrived in Government and was faced with questions of whether we wanted to continue the OA programme, there was no political will or leadership to maintain them. To the best of my knowledge OAs have now lapsed into nonexistence.

Data and iteration are key - My final-but-one suggestion is an emphasis on using data to inform iterative development of a programme. This is something I had less experience with in Government, but firmly believe in regardless. Thanks to the proliferation of mobile technology, all of us produces more personal data than ever before. We can also track habits and contact people instantly. The public sector has ben glacial to hop on the back of data as a means of better programme design, development and policy utilisation. Imagine if we could use data to better understand which teenagers go truant, or have mental health problems, or end up on drugs. Interventions should be able to both use data in concept but also learn from data as it’s being rolled out, because good projects that dont work first time can be improved (as opposed to thrown away and discontinued). Imagine if Opportunity Areas had properly tracked individual level outcomes pre- and post-intervention. We would be able to iterate a programme and hardness the forces that do work. Same with Children’s Social Care, where better use of data could really tell us who is at risk and how we can get to them. Again, going back to the Government’s response to Covid, data collection, management, and analysis allowed for the effective allocation of dialysis machines, and PPE (to an extent), as well as developing a better understanding of which groups were rejecting the vaccine. Data, in this instant, played a real role in saving lives!

Real change takes culture reform - Finally, real social policy reform has to be culturally embedded across an organisation, a cohort and perhaps even a population. Schools reform filtered across the teaching profession. Children’s Social Care reform did not (and consequently it hasn’t worked). Everyone has to buy in to a new way of doing things or delivering a service. Only once that happens will we really get big things done.