Does Welfare Work?

Does welfare benefit the people in receipt, or is it throwing good money after bad?

Summary:

We spend £313bn on welfare for working age claimants and pensioners.

There has been significant growth in welfare spending associated with sickness benefits (more than 1m more people are out of work on sickness benefits since Covid-19) and because more people age over the state pension age making them entitled to the Triple-Lock protected state pension.

Reform is necessary partly because spending will continue to grow out of control if more people sign-off sick. 6.4m are currently out of work on welfare, contributing to lagging economic growth (which we desperately need to reverse). If we want the economy to grow and poverty to fall, getting people off welfare and in to work is a good place to start.

A functional welfare system is a necessary part of a compassionate society and economy, however at the moment, the net is cast too wide. Fewer claimants able to access more generous entitlements, would be a better system in the long term. In a perfect world you would have a system that embeds the principals of contribution, incentives, and generosity. At the moment, the current system barely does one of those things.

The welfare budget is once again under the microscope in Westminster as low-growth and subsequently low tax-revenues have forced this Government to look for cuts to public expenditure. Welfare can be crudely split in to two sections (although there is some overlap); working-age benefits, and old-age pension support. In the past, the focus has been on cutting the working-age welfare bill (although several administrations have looked at increasing the State Pension Age). This is partly because British public opinion has been more favourable towards pensioner entitlements, and less favourable towards what some consider the ‘shirkers and scroungers’.

This all raises a load of questions; how much do we actually spend on welfare (working age and old-age)? Is there wastage in the system? What is the purpose of welfare spending and does it deliver a positive social and economic return on investment?

How much do we spend on welfare?

The Office for Budgetary Responsibility (OBR) published its most recent Economic and Fiscal Outlook in March 2025. For the current year 2024/25, it forecasted total welfare spend at £313bn (according to table 4.7 in the detailed forecast table on expenditure). The largest component of that figure is the State Pension (£137bn), Universal Credit (£52bn), Sickness Benefits (£46bn), Housing Benefit (£14.7bn) and Child Benefit (£13.3bn).

Working age welfare is means tested and focuses support on (again, crudely, with plenty of overlap) 4 groups:

People with no income or low incomes - eligible for Universal Credit (UC).

People with children - eligible for child benefit, child element of UC, and free hours of childcare.

People who cannot afford housing - eligible for housing benefit (also now an element of UC).

People with an illness or disability - eligible for Personal Independence Payment, Disability Living Allowance, Employment and Support Allowance and Incapacity Benefits.

There are a suite of other entitlements; Winter Fuel Payments, Attendance Allowance, Carer’s Allowance, Statutory Sick Pay, Statutory Maternity Pay etc etc etc. These payments are a relatively small share of the total welfare bill. So for the purposes of a broader conversation about welfare (and specifically working-age welfare), its efficacy and wastage in the system, I will stick to the entitlements above.

The first thing to say about current welfare spending is that it has increased considerably in relative terms over the last 70 years (see chart below). In the 1950/60s we spent between 5-7% of GDP on social security. Since the turn of the millennium it has fluctuated between 10-12% of GDP. While welfare expenditure growth as a percentage of GDP has softened in recent years, it has increased substantially in nominal terms over the last 10 years. In 2014/15 OBR forecast total welfare spend at £214.5bn. The only budget that has expanded at a faster rate (as a proportion of GDP) is the healthcare budget (which has nearly trebled as a share of GDP since the early 60s).

What has driven growth in welfare spending?

A lot of that growth in social security spending has been driven by two factors:

In the short term, higher rates of sickness benefit dependence.

Over the long term, our ageing population (which has increased spending on the state pension).

Sickness benefits

The first thing to note is that there has been an uptick, post-Covid, in the number of people on ‘out of work’ working age welfare. In February 2013 there were 1.5 million people on Job Seekers Allowance (unemployment benefits) and 2.4 million on Incapacity Benefits - a total of 3.9 million on ‘out of work’ welfare. As Universal Credit replaced JSA and IB, this number increased to 4.8m (as of November 2024). That’s 1 million more people out of work and on UC, and almost all of that growth is related to ill-health. On top of 1.5 million people still on incapacity benefits, 6.4 million people are currently on out of work benefits.

The sickness benefit case load at DWP has risen from 2.2 million in 2018/19 to 3.5 million in 2024/25. The proportion of people in Britain with a disability has somehow grown to 1-in-4. Remarkably, 1-in-10 working people now claim some kind of sickness benefit. The costs associated with this are astronomic; in 2024/25 DWP forecast Personal Independence Payments at £26bn, UC (health-related unemployment) at £16bn, Incapacity Benefits at £12bn, housing benefits for people with ill-health at £14bn, Disability Living Allowance at £8bn, and Carers Allowance at £6bn. For all ages (working age and pension age support) total sickness benefits are estimated to cost £93bn.

There are some interesting aspects to this trend. To claim sickness welfare you have to go through a Work Capability Assessment. At the WCA your health condition is recorded; 69% of all WCA conditions recorded for sickness benefits are ‘mental and behavioural disorders’, almost 50% more than ‘musculoskeletal’ issues. The other concerning aspect to this sudden rise in sickness claimants with mental health and behavioural disorders keeping them out of the labour market, has been the disproportionate number who come from low-income households. Of course, this raises questions of whether people from low income households are driven in to welfare, or whether welfare drives them in to lower income brackets (we address this later).

A lot of the data used for this blog comes from Fraser Nelson’s microsite https://www.benefitstrap.com/ - which he set up to sit beside the Channel 4 documentary charting this phenomenon occurring in our society.You can watch that documentary below:

Ageing Society

Over the long term, one of the primary drivers of higher spending on welfare has been the growth in the number of people over the state pension age. We now have more people over the SPA, claiming both sickness benefits, low income support, and the state pension, than at any point in our history. This is part of what is commonly understood as the ‘Ageing Society’. As a result, state pension spending has increased dramatically over time.

The situation is only expected to get more extreme. In March of this year, the Lords Select Committee on Economic Affairs, said: “With life expectancy increasing, the UK can expect 27 per cent of its population to be over 65 by 2072, compared to around 19 per cent in 2022; the percentage of the population over 85 (around 2.5 per cent in 2022) is set to nearly double and reach approximately 3.3 million by 2047”.

How generous is our Welfare System?

There are two reasonable ways to look at ‘working-age’ welfare generosity. Firstly in nominal terms relative to income earners. In this respect, the system is generous to people on sickness benefits and those with children. If you are single and unemployed, the return on ‘sitting-at-home’ claiming benefits is relatively low. Unemployment benefits are some of the lowest in the OECD. However if you are single with children and claiming some element of disability benefits, you will be better off than someone on the average wage in the UK.

It’s also worth noting that the relative generosity of our system increases over time. The UK system, unlike many other countries, pays as much to someone in their 5th year of dependency as it did in their 2nd month (see below). This goes against the principle of a contributory system, and one with inbuilt incentives to encourage people off welfare.

The second way to compare generosity would be to look at comparable countries. In this regard, the UK is somewhere in the middle. As we mentioned earlier, the welfare spend is approximately 12% of GDP, this is lower than USA, Italy, France and Germany, but higher than Canada, Sweden and the Netherlands.

Separating out non-pensioner benefits between sickness and ‘other’ benefits, the OECD chart below shows the UK system slightly more generous when it comes to ‘other’ benefits (which you can assume to mean childcare, child benefit, housing etc). This doesn’t chime with a lot of analysis on the generosity of the British childcare support which shows it to be low by international standards. Although admittedly housing benefit in Britain is much more generous than other countries, mostly because our housing market is much more expensive.

Finally, on pensioner benefits… the SPA is really quite generous due to the decision to uprate the state pension consistently through the Triple Lock. The OBR outline how the Triple Lock works well for claimants; “The state pension is uprated each year in line with the ‘triple lock’ that states it will rise by the highest of CPI inflation, average earnings growth or 2.5 per cent. This is a more generous uprating policy than for working-age benefits and tax credits or child benefit”. Unsurprisingly state pension claimants have ended up doing better than other people in the welfare system; “The standard full amount of means-tested support available through pension credit for a single person above SPA is 2.5 times the amount available for a single person out of work below the SPA through universal credit or jobseeker’s allowance” (IFS).

Does the welfare system benefit claimants?

We need to ask the question too, does welfare support people on it? The answer is yes, sometimes, but not all the time. Clearly a more generous state pension, paired with sickness benefits and housing wealth, has resulted in a massive reduction in pensioner poverty (see above). Equally, Universal Credit’s dynamic character, paired with less generous entitlements for single people out of work, has pushed lots of people who would have been stuck on benefits, back in to the work place. Our labour market has been one of the strongest in the western world, before and after Covid-19.

However, there are aspects to welfare which are less supportive for claimants. Currently too many people are getting stuck on sickness welfare (largely as a result of mental ill-health) and not getting back in to work. More ESA and PIP claimants are not being reassessed, and when they are it is over the phone, which can often lead to automatic asymmetric levels of information.

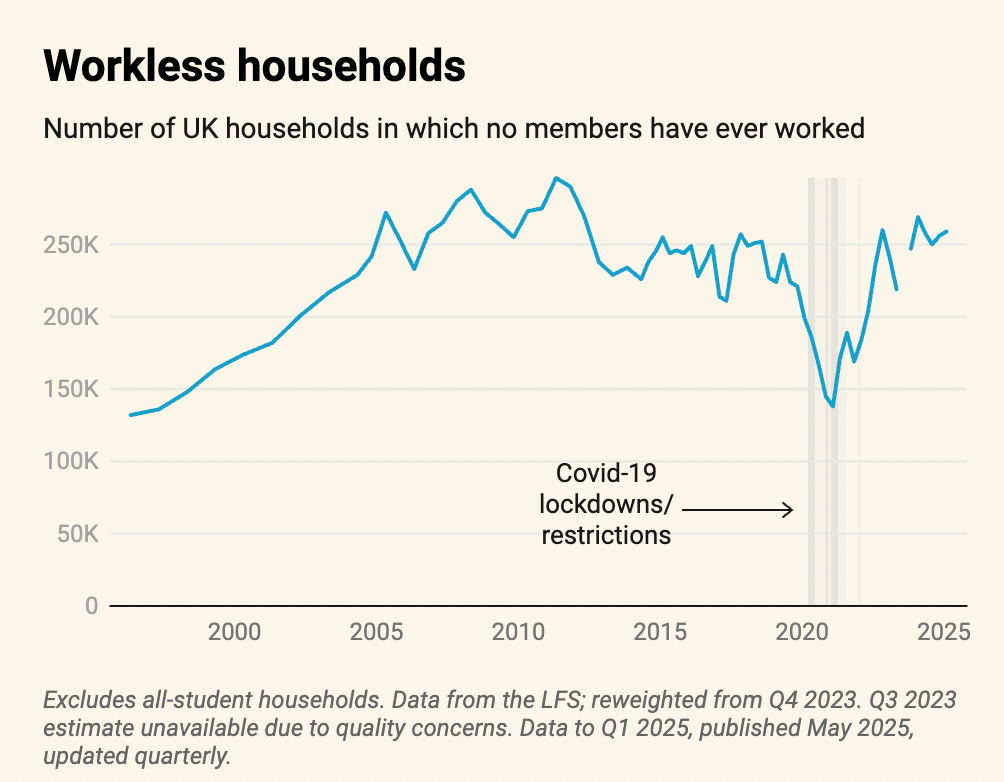

Where the number of workless households in the UK had halved between 2010 and 2020, since Covid that number has spiked again. Unemployment is bad for anyone, but it can be really bad for people with mental health problems and children. We know unemployment compounds someone mental health problem, and children growing up in workless household are themselves more likely to fail at school and end up unemployed.

The obvious answer to the criticism above is that if the welfare system were more generous, people would get better and get back in to work? I haven’t seen any of that evidence to suggest more generous payments induce pro-social behaviour. Incentives to get back in to work tend to work the other way around, ensuring someone is always better off in work than they would be on welfare.

Conclusion

So Liz Kendall has laid out “plans to cut disability and sickness-related benefits payments to save £5bn a year by 2030”. Firstly, when talking about the overall size of the welfare bill, this would equate to a cut of less than 2%. The cuts are also in the area of welfare spend that has grown uncontrollably in the last few years. There is no rational justification for a doubling of people on sickness benefits in the last 5 years. It is not reasonable to blame ‘mental health and behavioural issues’ for the rise in worklessness and ignore the fact that claimants are overwhelmingly coming from low income and deprived communities. This is not a statistical anomaly, nor is it a normal trend. There is something wrong with the system here.

I have written at length at our big our Government has become. Rob Colville wrote a superb piece in the Sunday Times recently on the lunacy of our public finances, saying that we have been “spending like crazy… spending money we don’t have”. He calculated Government spending to equal “£23,757 for every adult in this country: roughly two thirds of the median full-time salary of £37,500. That includes £3,807 on health, £5,817 on welfare and pensions and a shocking £1,955 for that debt bill”. It therefore makes eminent sense to look at how the welfare system, that eats up £1 in £4 spent by the Government.

A modern and compassionate society needs a fair and effective welfare state to support people who are old, genuinely sick or facing short term financial hardship. However currently too many people claim welfare; “some 9.9 million working-age people, 22.8 per cent of the working-age population, are receiving some form of benefits”. I also recognise that the heavy lifting in this area needs to be done by the labour market, creating more highly paid jobs. More than 1/3rd of all UC claimants are ‘in-work’. Which is why a lot of this comes down to creating an economy that grows!

None of the above though points to increasing the scope and size of the welfare state, and certainly without first taking steps to boost economic growth and reduce our deficit. In a perfect world you would have a system that embeds the principals of contribution, incentives, and generosity. At the moment, the current system barely does one of those things.